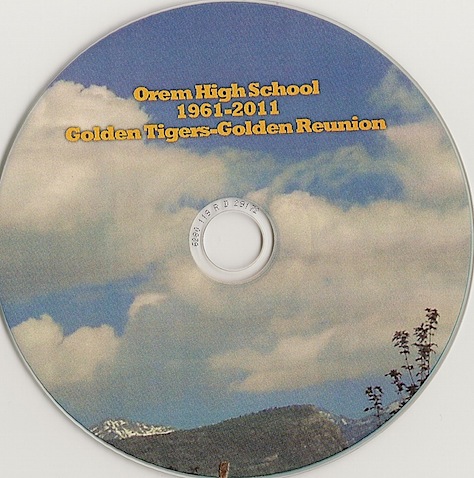

Au moment des retrouvailles du mois dernier en Utah, alors que je rencontrais de nombreux amis et de nombreuses amies d’autrefois que je n’avais pas vus depuis 20, 30, 40 ou parfois 50 ans, une question était sur le bout de toutes les lèvres : « Comment, batinse, se fait-il que tu sois rendu au Québec ? » [traduction libre]. Hummmmm, comme si un homme n’avait pas le droit de changer de pays, de langue et de culture!

Ma réponse ne tarda jamais à venir : « Ce serait un peu long à expliquer; lis la bio qui se trouve sur le CD que tu viens de recevoir. La mienne est là avec les 124 autres! »

Peut-être y a-t-il d’autres qui se posent cette même question à mon sujet, mais qui n’ont pas accès au CD. Pour eux, voici le court texte soumis à l’occasion du conventum des 50 ans de la promotion de 1961.

What ever became of Dean Louder?

In Mr. Dean Rigby’s eighth grade English class at Lincoln Junior High School, somethinghappened which changed my life. A seed of passion was sown which, when germinated, would lead me away from my roots, my homeland, and on a life-long journey among the French speaking peoples of the world, in general, and of the North American continent, in particular. I was deeply touched by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, Évangeline, which Mr. Rigby made us read aloud in class. This classic from American literature celebrates the mythical Acadian lovers, Gabriel and Évangeline, separated by the vicissitudes of war and the cruelty of the British who inflicted upon their people in 1755 an overt form of ethnic cleansing by scattering them to the four winds, like slaves, aboard vessels hired for that purpose. Two and one-half years spent in France (1962-1964) provided me with the opportunity to master the language of Molière, which eventually led me to that spoken by Gilles Vigneault (Québec’s poet laureate)—which is in reality the same language sung with a different accent—to that spoken by Herménégilde Chiasson (Acadian film maker, cultural broker and heir to Acadie ’s Évangeline)—which is also the same idiom spoken differently—to those of Zachary Richard (Louisiana troubadour) and Clifton Chenier (king of zydeco) whose Cajun and Creole sounds have enriched the North American music scene for generations.

After schooling at Brigham Young University and University of Washington, I accepted, in 1971, a position as professor of geography* at Université Laval, located on the banks of the St. Lawrence in far away Quebec City (150 miles downriver from Montréal). This is where we reared eight children (four boys/four girls), usually speaking English at home but nearly always French everywhere else. Today, these children and their children are spread across Canada, with a couple of daughters residing in the United States—in the capital city of Idaho which bears the lovely French name “boisé” meaning forest, wood or grove.

I feel a profound respect for my origins and harbor in my heart and head the fondest ofmemories of you all, but after forty years in la belle province, Québec is my home!

*You may ask, “what is a geographer?” I reply, “a wonderful profession which allowed me to earn a decent living doing what I love.” Here is how it happened. As a tiny tot, I loved geography. When I was 6 or 7, my parents gave me an atlas and gazetteer. I wore it out turning the pages, fingering the plates, rubbing the maps, memorizing the place names. On the other hand, I have never been a fan of National Geographic Magazine which skews the study of geography.

Until I returned from France, however, I didn’t know you could major in geography and become a geographer. I happened on to it quite by accident. Arriving home from France in September 1964, I entered BYU that fall a couple of weeks late and needed courses to start filling general education requirements. I wanted a history course being offered in the Heber J. Grant building. When I arrived, the course was closed. Frustrated, I stuck my nose in the room next door where there were plenty of seats available. Asking what it was, one of the students said « geography ». That was enough for me! I sat down, enjoyed the first lecture, the rest of the course and the rest of my life as a geographer. After the B.A. at BYU (1967), I attended University of Washington for the M.A. and Ph.D. (1967-1971), then headed for Québec.

En tant que géographe, je m’intéresse à la question de la mobilité géographique des êtres humains. Voyons voir ce phénomène tel que vécu par les hommes et les femmes de ma cohorte.

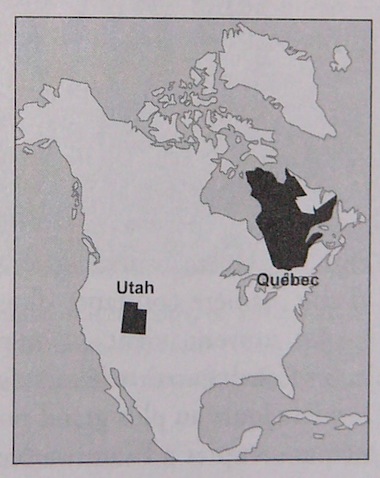

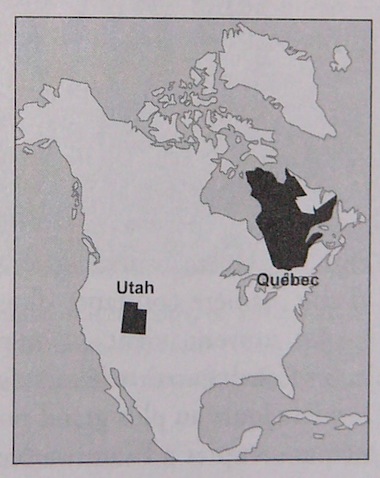

Distribution géographique en 2011 des membres de la promotion de 1961

Orem High School (n=267)

Monde

États-Unis 265

Canada/Québec 1

Australie 1

États-Unis

Alabama (1), Alaska (1), Arizona (9), Californie (15), Colorado (9), Illinois (1), Indiana (1), Kansas (1), Kentucky (1), Maryland (1), Massachusetts (1), Missouri (4), Montana (1), Nevada (4), New Mexico (1), Caroline du Nord (2), Orégon (5), Pennsylvanie (2), Caroline du Sud (1), Tennessee (1), Utah (194), Washington (5), Virginie occidentale (1), Wyoming (3).

Sommaire : 73% des finissants de 1961 habitent l’Utah, 89% les onze 11 États de l’Ouest.

Utah

Comtés : Box Elder (1), Cache (3), Davis (6), Emery (1), Iron (1), Juab (2), Millard (1), Salt Lake (38), Sanpete (7), Sevier (1), Summit (1), Tooele (1), Uintah (1), Utah (115), Wasatch (1), Washington (6), Weber (8).

Sommaire : 43% des finissants de 1961 habitent le comté d’Utah; 59% de ceux qui habitent l’État de l’Utah habitent le comté d’ Utah.

Comté d’Utah

Villes : American Fork (5), Benjamin (2), Eagle Mountain (1), Elberta (1), Genola (1), Highland (2), Lehi (4), Lindon (7), Mapleton (2), Orem (52), Payson (5), Pleasant Grove (8(, Provo (11), Salem (2), Springville (7), Spanish Fork (5).

Sommaire : Un finissant sur 5 de 1961 habite encore Orem, 50 ans plus tard. 45% de ceux qui habitent le comté d’Utah habitent Orem.